Christ’s Descent Into Hades

1. Hell and Hades in Biblical Literature

The terms “Hell” and “Hades” are often used interchangeably by English translators.

This unfortunate tendency is a product of Western influence. While Latin has both the

words infernum and gehenna, the former served as the normative term in the West to

refer to the lower regions, the abyss, and hell interchangeably, without differentiation.

Yet, the Greek terms Hell (gehenna) and Hades (hadēs) are used with clear delineation in

Jewish tradition, in the NT, and in the Eastern Church fathers.

In Josephus’ Dissertation on Hades, he lays out the common Jewish understanding of the doctrine in literal terms. Hades, Josephus tells us, is a subterranean region into which

the souls of the dead, righteous and wicked, enter. The righteous and wicked are

separated by angels, who tend to these souls as they all await judgment. The condition

of the righteous is pleasant, while that of the wicked is unpleasant. Josephus also

mentions a lake of fire into which the wicked are cast after the final judgement, but he

is clear that no one is yet in this lake, since the judgment has not taken place1.

The NT uses both gehenna and hadēs, but the terms are not interchangeable. Their uses instead reflect the Jewish lore explained by Josephus. In the parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31), for example, Jesus speaks about hadēs (16:23), not gehenna. The Rich Man lifts up his eyes in Hades and sees Lazarus on Abraham’s bosoms (16:24) — a picture of Lazarus reclining on his chest (cf. Jn 13:23). The Rich Man speaks of being in torment, and of being in a flame, and Abraham mentions a chasm between himself and the Rich Man. Although the parable does not state explicitly that Abraham and Lazarus are in Hades with the Rich Man, this is the implication of Jewish lore reported by Josephus, since this region is the post-mortem dwelling of both the righteous and the wicked. All three are in Hades. There, the Rich Man suffers, while Lazarus is comforted (by Abraham).

Peter’s Pentecost homily also mentions Hades and confirms the above reading, namely,

that it is the holding place for the souls of both the righteous and the wicked. He quotes Psalm 16:8-11 (LXX), which speaks about God not abandoning his Holy One to Hades (not Hell), nor letting him see corruption (Acts 2:27). Peter interprets this Psalm as a prophecy about Christ, since David’s body remains in the grave (subject to

corruption), and Peter’s hearers thus presume (as reported by Josephus) that David’s soul is in Hades. But, Peter continues, Christ’s soul was not abandoned to Hades nor his body to corruption. For God raised him from the dead (2:31).

The declaration that Christ was not abandoned to Hades is in keeping with the NT

theme that Christ was victorious over death and Hades. Christ prophesied that the gates of Hades (not Hell) would not prevail against him (Matt 16:18). Peter tells us that in Christ’s descent into Hades, he preached to those held in this “prison” (phylakē) (1 Pet 3:19) in order that they might “live according to God in spirit” (1 Pet 4:6). And

Christ’s victory over Hades is, of course, manifest in his Resurrection and proclaimed in both Peter’s Pentecost homily and Christ’s declaration to John that he holds the keys to death and Hades (not Hell) (Rev 1:18). These various passages converge to form the picture that death and Hades is a prison in which mankind was held prior to the advent of Christ; into this prison Christ entered and preached in order to liberate mankind; the gates of this prison did not prevail against him; and because of his victory over death, Christ now holds the keys to death and Hades.

The lake of fire from Jewish lore also appears in the NT, along with the sentiment that the lake is empty until the final judgment. In the book of Revelation, Hades (not Hell) gives up its dead in the universal resurrection for judgment (Rev 20:11-13). Only after the judgment is anyone — or thing — cast into the lake of fire. First death and Hades are cast in (Rev 20:14) and then the wicked (Rev 21:8).

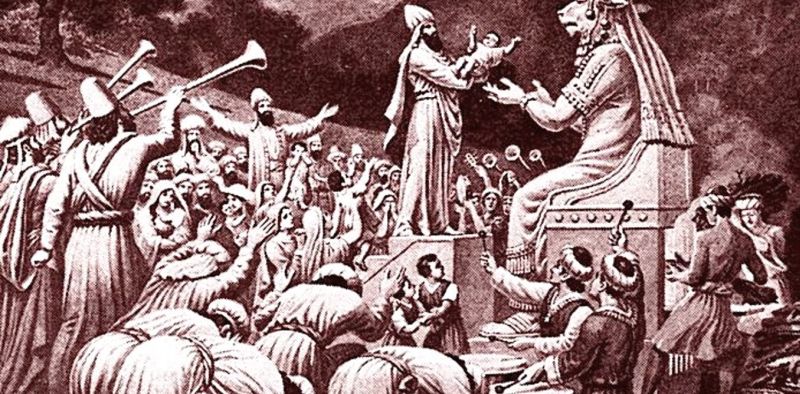

The biblical use of “Hell” (gehenna) evidently refers to the lake of fire —

though the word originally referred to

the valley outside of Jerusalem where

children were sacrificed to Moloch (cf.

Lev 18:21). The numerous NT

mentions of “the hell of fire” or “the

hell” or “hell” use the language, echoed

in Revelation, of being cast or thrown

into Hell (Matt 5:30 and Luke 12:5). And Christ explicitly associates gehenna with final

judgment (Matt 23:33). More importantly, however, these numerous references speak

of being thrown bodily into Hell, indicating a post-resurrection fate. Christ often draws

the contrast between those who can harm the body but not the soul and God who can

cast both body and soul into Hell; Christ recommends gauging out one eye to avoid

being thrown into Hell with two; or cutting off one hand, as opposed to being thrown

with two into Hell (Matt 5:30; 5:31; 10:29; 18:9; Mark 9:43, 45, and 47). In other

words, disembodied souls are not cast into Hell after death; souls and bodies are cast

into Hell after the resurrection and judgment. Presumably, this is the eternal fire

prepared for the Devil and his angels (Matt 25:41).

Biblical references to the “second death” refer specifically to the lake of fire (Rev 20:14; 21:8). The experience of the second death in the NT is identified with being cast into

this lake (Rev 21:8), an event that occurs only after the universal resurrection and the

final judgment (Rev 20:11-13). As mentioned above, such casting is first done to death

and Hades (Rev 20:14) and then to the wicked (Rev 21:8).

Finally, in the NT we also find

mention of Tartarus — the dark

abyss into which Zeus cast

Chronos and the Titans in

Greek mythology. This phrase

appears in 2 Peter 2:4, referring

to the place into which God

casts the fallen angels. There,

these angels were held by “chains of gloom” (seirais zophou) — or just held in gloom,

since the word “chains” does not appear in all manuscripts. Presumably this is the abyss

that the demons mention when pleading with Christ to not cast them out of

demoniacs (Luke 8:31).

By way of summary, then, the NT teachings about Hell and Hades draw a distinction

between these. Hades is the realm of the dead into which the souls of both righteous and wicked enter when the soul departs the body. Man, being captive to death prior to the advent of Christ, was held in this prison. There, the souls of the wicked suffered, while the souls of the righteous were comforted. The Devil and his angels, by contrast, were cast into the abyss of Tartarus after their rebellion, where they were held in

(chains of) gloom. As for Christ’s descent, his soul entered Hades after his crucifixion.

He preached to souls held captive there. In his resurrection, he was victorious over Hades, and liberated humanity from this prison — its gates did not prevail against him, and he now holds the keys to death and Hades. Hell, by contrast, refers to a lake of eternal fire prepared for the Devil and his angels. Into this lake none are cast until after

the final judgment. At the resurrection, Hades is emptied of whatever souls remain within it and all are judged in the body. Following the judgment, death and Hades are cast into the lake of fire, which is the second death, and then the wicked too are cast bodily into the lake of fire, which is the second death.

2. Hell and Hades in the Eastern Church Fathers

In Eastern patristic literature, we find the very distinction between Hades and Hell that appears in the NT. The Eastern fathers refer to Gehenna as a place of future judgment2 characterized by fire. And to be cast into Gehenna after the final judgment is to experience the second death3.

Now, Alexandrian Judaism, with its allegorizing tendencies, rejected the literal

interpretation of Jewish lore reported by Josephus. Philo of Alexandria, for example,

suggests that Hades is a metaphor for the condition of the soul. Hence Philo, after

declaring that there is no subterranean region beneath our feet, says that Hades refers

to the condition of the wicked, who wander about in vice apart from God. This

condition is the true Hades, says Philo4.

The Eastern Church fathers, like the Alexandrian Jews, likewise interpret the biblical

images as allegorical pictures of deeper truths. Many read the eternal (or uncreated) fire

as God’s own love and presence5 — which is why this fire (a common picture of God 6) is

eternal. Yet, this fire has a double effect, “one that burns, and another that illumines”7.

The difference, Basil tells us, is not located in God but in the respective conditions of

the righteous and the wicked: “The evils in Hell do not have God as their cause, but we

cause them.” Just as the sun scorches bad soil while causing good soil to flourish, so the

presence of God is joy to the righteous but pain to the wicked8. Hence, how one

experiences the glory of God is based on the “quality of his disposition9”.

Whether the condition of the wicked described in the second death is permanent is a

matter of dispute amongst the Eastern fathers. The majority view is yes, but St. Isaac of

Syria sees even Gehenna as “belonging to mercy” and God’s “eternal goodness,” with

its end being purification10. Gregory of Nyssa, likewise, holds out hope that those who

suffer the condemnation of Gehenna might still be led ultimately into the final restoration of the Kingdom of Heaven11. Regardless, even those Eastern fathers who

oppose such views, believing Hell represents a final and irreversible state, do not locate

the permanence of damnation in God, but in the creature. Chrysostom, who certainly

believes Gehenna to be permanent12, locates this permanence in the creature’s refusal

to repent. In his exposition of the “unpardonable sin,” Chrysostom points out that

Christ does not say the sin is per se unpardonable but that it won’t be pardoned,

indicating that pardon is possible — as with all sins — but those who commit this sin

refuse to repent of it. Hence, as C. S. Lewis’ well-known phrase puts it, Hell is locked

from the inside. For God calls all to salvation, but he never deals forcibly or coercively

with anyone13.

Regarding Hades, the Eastern fathers have far more to say, precisely because of the

doctrine of Christ’s descent thereto. Like the NT, the Eastern fathers identify Hades as

the realm of the dead, equating it with Sheol of the Old Testament. As for who is in

Hades, they are clear that, because death came to all men through Adam, Hades held

both the righteous and the wicked, prior to the advent of Christ14. There, in Hades, all

sat in darkness. The wicked suffered, while the righteous were comforted as they waited

for Christ, the door to the Father15.

Several Eastern fathers suggest that the

preparation for Christ’s own descent began well

before the advent of Christ. Both Chrysostom

and Origen speak about the OT prophets

preaching to the dead about Christ’s future

coming16. And both Origen and Gregory of

Nazianzus teach that John the Baptist, who was

the forerunner of Christ on the earth, was also

his forerunner “under the earth,” preaching to

souls in Hades about the quickly Christ who was

soon to come17.

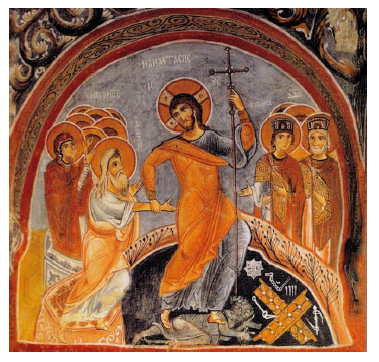

Now, regarding Christ’s descent into Hades, the Eastern fathers consistently treat it as salvific — as significant to the salvation of humanity as his Crucifixion or Resurrection.

By descending into Hades, Christ saves humanity from death and Hades18. The

underlying rationale is this. Christ’s descent destroys death because, being divine, he

bears in his person Eternal Life. Hence, when Christ enters Hades, Life enters the

realm of the dead19. Both Chrysostom and John of Damascus speak about the light of Christ destroying the darkness of Hades — the Sun of Righteousness filling it, his

deified soul, shining forth the uncreated light of God into its darkness20. So, just as

created light destroys darkness, so the divine light and life of Christ in Hades destroys

its darkness of death. For this reason, the Eastern fathers also speak about Christ

transforming Hades from dark and joyless into paradise. Chrysostom sees this in

Christ’s promise to the thief on the cross. Christ could promise the thief that he would

be in paradise today, even though they would both descend into Hades — Christ stating

plainly after his Resurrection that he did not yet ascend to his Father (Jn 20:17). The

paradise the thief was promised was in Hades, for there the light of Christ would shine,

making that place into paradise21.

The undoing of death in Christ’s

descent also informs how the Eastern

fathers understand Christ to have

defeated the Devil, who holds the

power of death22. Gregory of Nyssa

famously describes the defeat of Satan

using a “fish hook” metaphor. The

Devil, catching glimpses of divine

light within Christ’s flesh, is enticed

to lay hold of him, like a fish drawn

to bait on a hook. Seeing the Son of

God veiled in mortal flesh23, Satan

cannot resist the prospect of killing

him. But what the Devil does not

realize is that, in delivering Christ to Hades, Christ will undo death, and thus

overthrow Satan’s power over humanity, bringing life to the dead24. In this way, Christ

binds the strong man (the Devil) and plunders his house (Hades)25.

This “plundering” is depicted by the Eastern fathers as Christ emptying the tombs of

Hades26 and breaking its gates, as he prophesied27. For the gates of Hades held

humanity within the prison (phylakē) of death28. In breaking these, Christ liberated all

those held there — that is, the whole human race. For the Eastern fathers are clear:

Christ descended in order to save all of humanity29. In this light, the phrase of Lewis —

that Hell is locked from the inside — is too strong. For it suggests that there is still a

door between humanity and God. According to the Eastern fathers, the gates of Hades

have been destroyed. The more appropriate picture is of a former prison in which all

the bars have been removed and destroyed. If any remain within the prison, it is not

because of a gate.

In addition to transforming Hades and plundering it, the Eastern fathers also speak

about Christ preaching to the souls there, drawing on 1 Peter 3:19. They speak about

Christ appearing to the dead in Hades, just as he appeared to the mortals upon the

earth30. And there, in Hades, Christ preached to them, righteous and wicked alike,

converting all who were willing to receive him31. Now, whether all did in fact receive

Christ is a question that most Eastern fathers pass over in silence. They confidently

affirm that the OT Saints received Christ, since it was him whom they anticipated and

awaited32, but the Eastern fathers make no dogmatic assertions about the wicked. The

wicked were liberated with the righteous; Christ preached to the wicked; he did so in

order to save them; and as many as received him were saved33. On this they agree. But

whether none, some, or all of the wicked did in fact receive Christ and exit Hades is a

matter that few Eastern fathers speculate about.

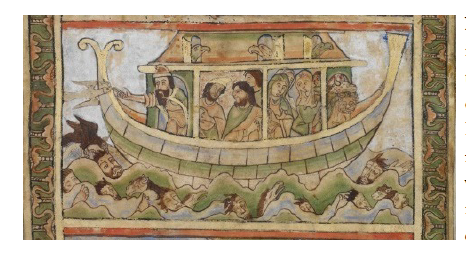

Maximus the Confessor illuminates the liberation of

the wicked in Hades in his

comments on 1 Peter 4:6.

He explains that those who

rebelled in the time of Noah

were judged in the flesh as

men (drowned and their

disembodied souls were cast

into Hades) so that they might live according to God in the spirit (at the preaching of

Christ). Maximus here echoes the Eastern patristic theme that death is a divine mercy,

which unmakes corrupted man, so that we might be remade incorrupt in the

resurrection from the dead34. So, in the same way, the wicked in the time of Noah were

unmade by their drowning, so that they might be made alive by the preaching of Christ

and remade incorrupt in the resurrection35. So it is for all the wicked held in Hades.

Yet, whether the wicked receive Christ and the life he offers or not, the fact remains

that Christ’s descent has transformed Hades, liberated all, and opened the way back to

the Father of Lights.

Though Hades is more often than not depicted as a place, which is a prison, or “Satan’s

house,” in which humanity is held captive, Eastern patristic literature — and

iconography — also depicts Hades as a sentient being that swallows up humanity,

holding dead men captive within its belly. Arguably, this sentient depiction of Hades is

taken from Revelation, where Hades “gives up” — an active verb (adōkan) — the dead

within it and is later thrown into the lake of fire, a picture more easily associated with a

being than a cave beneath the earth. But regardless of the source, this

anthropomorphic image of Hades also plays a role in the Eastern patristic teachings on

Christ’s victory. We see it is poetically employed in The Gospel of Nicodemus, written

sometime between the 3rd and 5th centuries. Therein, we find the following dialogue

between Satan and Hades:

Satan, the prince and chief of death, said to Hades: Make yourself ready to receive

Jesus, who boasts himself to be the Son of God, whereas he is a man that fears death….

Hades answered and said to Satan the prince: Who is he that is so mighty, if he is a

man that fears death? For all the mighty ones of the earth are held in subjection by my

power, even they whom you have brought me subdued by your power. If, then, you are

mighty, what manner of man is this Jesus who, though he fears death, resists your power? …

But Satan the prince of Tartarus said: Why do you doubt and fear to receive this Jesus

which is your adversary and mine? … Hades answered and said: You have told me that

it is he that has taken away dead men from me [e.g., Lazarus]…. Satan the prince of

death answered and said: It is the same Jesus. When Hades heard that he said to

him: I adjure you by thy strength and mine own that you bring him not to me.

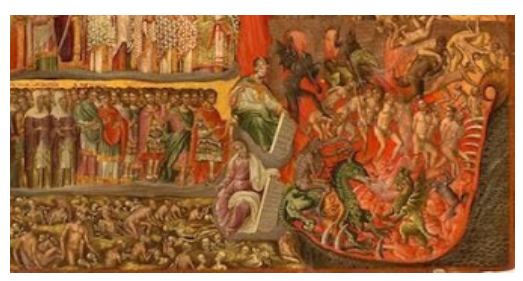

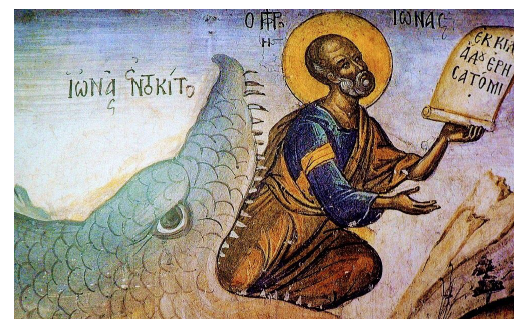

In Eastern Christian iconography, this

sentient Hades is depicted in what is

sometimes (inaccurately) called the “Hell

mouth” in the icon of the Final Judgment

icon. In the lower right corner of the icon

is the head of a large monster, from

which comes the dead for judgment. In

some (rare) icons of the Resurrection,

Christ is depicted as coming forth from

this same monstrous head, bringing with

him Adam, Eve, and others who have

died. And this same head appears in the

icon of Jonah. In keeping with Christ’s

own words that Jonah is a picture of his

future descent into “the belly of the

earth” (that is, into Hades) (Matt 12:40), Eastern Christian iconographers often depict

Jonah in the garb of Christ, coming forth from the fish that is depicted as Hades, the

same monstrous head we see displayed in the icon of the Final Judgment.

It is this monstrous Hades whom Chrysostom, in his famous Paschal homily, speaks of

as repeatedly “embittered” (pikrainō) — a term of sentiens — because it took into itself a

body but encountered God; it took into itself earth and encountered Heaven; it took

into itself the visible and encountered the invisible36. The picture is an inversion of a

living body taking into itself poison, which communicates to it death. In this case,

Hades, who is the embodiment of death, takes into itself Him who is Life, and this

Christ communicates life to all within it. The defeat of Hades that follows is the

Resurrection of Jesus37. This event of events is anthropomorphized as Hades vomiting

up Christ, since it cannot digest him who bears in his person Life itself38. In this defeat

of Hades, Christ thus demonstrates that death has no dominion over him39, as he steps

forth as the first fruits of the Resurrection from the dead, showing us the way of

resurrection40. And while Christ descended alone, he rose and ascended with many.41

Now, as with Hell, the imagery of Hades is read in an allegorical way by the Eastern

fathers, which is why they are untroubled by the idea that Hades might be depicted in

multiple ones — sometimes as a place and other times as a being. Macrina, when

speaking to her brother, Gregory of Nyssa, offers a reductio ad absurdum as to why Hades

cannot literally be “under the earth.” As she points out, the dwelling of spirits is the air,

and the earth is a sphere. Hence, the air under the earth is the same air above the earth.

So, when the soul leaves the body and enters “Hades,” its spatial location is a matter of

indifference; the fact that it has departed from the body is what locates it within the

realm of the dead42. Gregory of Nyssa also finds fault in the literal reading of Hades as a

place with an unbridgeable gulf between the righteous and the wicked. As Gregory

points out, the Rich Man and Lazarus are portrayed as standing on either side of this

gulf, and yet they are able to speak to one another. Rejecting the gulf as spatial, Gregory

interprets this divide as the unbridgeable spiritual gulf between the righteous and the

wicked, between virtue and vice43. Hence, much like the allegorical readings of

Gehenna, the great divide is based on the differing conditions of the souls, not their

location. This same line of thinking also echoes in Chrysostom, who, as mentioned,

points out that Christ promises paradise to the thief on the day of his death, but they

do not ascend to the Father. Rather, it is in Hades that the thief experiences paradise,

for Christ is there with him. A place called Paradise is not what is promised, but the

spiritual condition, for the Kingdom of Heaven is within (cf. Lk 17:21)44. Likewise,

Chrysostom is clear that the “gates of bronze” that Christ breaks are not in fact bronze,

as if a craftsman shaped gates for Hades; rather, the imagery of bronze gates is merely

illustrative of the mercilessness hold of death upon humanity; it is this hold that Christ

breaks45. Likewise, Macarius suggests that the true descent of Christ is into the human

heart, which was long held by death, and there, within the heart, Christ commands

death to release us. This descent, says Macarius, is a present reality for all of humanity

for all time, likened to the rain that God sends upon the just and the unjust alike46. By

this descent into the heart of humanity, Christ has healed our nature and reopened the

way to ascend back to God our Father.47 Or to employ the image of Hades as a prison,

discussed above, Christ has forever destroyed the gates of this prison. There are no

bars; all have been liberated; and the way back to the Father of Lights remains open to

all people of all times and all places — even though we must freely embrace this

freedom and follow Christ out of Hades.

3. Hell and Hades in Western Christian Literature

The Western doctrine of Christ’s descent develops in considerably different ways. First, as noted above, the Latin writers do not distinguish Hell and Hades. Hence the Latin

doctrine develops as a Harrowing of Hell,

not Hades. Early aspects of the Western

doctrine in Hilary, Jerome, and Ambrose

mirror aspects of the doctrine in the East.

Christ smashes the gates of bronze, liberates

those within, and brings life to many.

Jerome even echoes the “fish hook” theme

from Gregory of Nyssa.

However, a change occurs with Augustine of Hippo. Augustine finds it unacceptable to

think that, prior to the advent of Christ, angels would carry the patriarchs into “Hell,”

as stated in Christ’s parable about the Rich Man and Lazarus — here reading Hades as

Hell. Hence, Augustine distinguishes “Abraham’s bosom” from “Hell,” suggesting that

the former was really a lesser paradise. This, of course, raises the question for Augustine

of whether Christ descends into both Hell and Abraham’s bosom, a question previous

authors did not ask because these were not seen as two different “places.” Augustine

affirms that Christ certainly descended to Abraham’s bosom, but he hesitates to say

that he descended into Hell. Augustine ultimately entertains the idea that Christ also

descends to Hell in order to liberate some who, by God’s mysterious justice (by which

he means predestination), he chose to liberate. But unlike the Eastern Church fathers,

who suggest that Christ liberates all, Augustine rejects such a view as absurd. Those that

did not believe on earth cannot find faith in Hell, says Augustine. As for the Eastern

view that Christ’s descent is a cosmic event for all peoples of all times, we see a stark

contrast in Augustine. He sees Christ’s descent as a one-time event that is relevant to

only those in Abraham’s bosom and those in Hell at the time of this descent; it has no

significance beyond this single moment in time. According to Augustine, the memory

of Christ’s descent was in fact obliterated after his departure. Hence, it has no lasting

effect for those who remained in Hell nor for those who descend there after Christ’s

ascent in the Resurrection.

Augustine’s views took on further weight when echoed by Gregory the Great. Like

Augustine, Gregory takes the declaration that Christ conquered Hell as hyperbolic,

rejecting the idea that he liberated all. Echoing Augustine, Gregory insists that one

cannot find faith in Hell if one has not believed when upon earth. As for who Christ

liberated, Gregory’s answer is the same as Augustine. He brought life to the righteous

in Abraham’s bosom, and if he liberated any from Hell, he did so only in keeping with

his mysterious election.

The doctrines of Augustine and Gregory were further codified in the West by the

council of Toledo in 625 AD. In the years to follow, conflict emerged between Pope

Boniface and an Irish missionary, Clement, over these Western revisions to the

doctrine. Clement insisted, in keeping with the East, that Christ did indeed liberate all

of humanity, regardless of whether these souls were believers or unbelievers when upon

the earth. Boniface convened a synod in Rome to condemn this view and reiterate the

view of Toledo — also held by Augustine and Gregory — that Christ liberated only the

OT righteous.

In the medieval period, the Western doctrine continued to develop in idiosyncratic

ways. Augustine’s distinction between Abraham’s bosom and Hell had already

introduced the notion of three spiritual regions: Heaven, Hell, and the lesser Heaven of

Abraham’s bosom. The medievals came to refer to Abraham’s bosom as a limbo, or

middle place, between Heaven and Hell. Hence it became known as the “limbo of the

fathers” (limbus patrum). But there emerged a second limbo in Western medieval

thought. Later medievals were less inclined than Augustine to grant the damnation of

unbaptized infants. Hence, there emerged the doctrine of a “limbo of infants” (limbus

infantium). The rationale for differentiating this limbo from the limbo of the fathers was

that the fathers believed and attained righteousness, while unbaptized infants simply

lack personal sins that merit damnation. While unbaptized infants are rightly kept from

the lowest Hell, they should not be elevated to the limbo of the fathers.

In addition, the medievals took further steps in developing the doctrine of Purgatory than previous writers. While earlier fathers spoke of post-mortem purgation of souls,

the medieval doctrine of Purgatory developed the doctrine into a formal “place” and

thus a further region of Hell48. In Purgatory, believers who fall short of beatitude

undergo penal suffering in order to purge the soul and deliver them to Paradise.

By the time of Thomas Aquinas, then, we find a doctrine of not only Paradise and

Hell, but of four regions of Hell. The lowest region is that of the damned. Above this

we find the other Hells. There is the Hell of infant limbo, where the souls of

unbaptized infants can never attain beatitude because they cannot attain baptism postmortem.

Yet, their pangs are less than those of the lowest Hell. In addition, there is the

Hell of the patriarchs (i.e., Abraham’s bosom), where the OT righteous awaited

liberation. There is also the Hell of purgatory, where believers who have received

baptism but still fall short of

beatitude, due to personal sins,

undergo suffering in preparation for

glory. Looking at Christ’s descent in

light of these developments,

Aquinas suggests that Christ

descended to either all the Hells or

into only the part where the

righteous were imprisoned. If the

former is true, Christ’s descent to

the lowest Hell would not be to

liberate the wicked, but to bring

shame to them for their unbelief. As

for the limbo of infants, this too

would not liberate, since only

baptism can cleanse original sin.

Liberation can only be offered to

the righteous who are already

prepared for everlasting glory49.

Such doctrines continued to inform the Roman Catholic teachings on Christ’s descent

for centuries to come. Such doctrines inform the romantic portrayals of the afterlife in

Dante’s Divine Comedy.

As should be clear from the foregoing, the differences between the East and the West on the doctrines of Hell and Hades are considerable. The East distinguishes Hell and Hades, while the West does not. The East teaches that Christ descended into Hades,

not Hell, while the West teaches that Christ’s descent is into Hell. The East teaches

that Christ’s descent was a cosmic event for all peoples of all times. The West teaches

that Christ’s descent was a one-time event. The East teaches that Christ’s descent

destroyed the power of Hades and liberated all of humanity from death — regardless of

whether all or only some choose to embrace this life. The West teaches that there are

numerous regions of Hell, and Christ liberated only those in one of these, while he left

bound those in the lower Hells of damnation and infant limbo. The East teaches that

Hades is forever transformed and defeated by this descent, the way back to God being

forever reopened. The West teaches that the memory of this one-time event was erased

from those left, as it had no bearing on their fate. The East sees in the various pictures

of Hades and Hell allegorical pictures of spiritual realities; the West sees a literal

depiction of various regions to which souls are bound post-mortem. Perhaps most

important, the East sees in Christ’s descent a critical feature of the gospel of his

liberation of humanity from death, while the West sees a one-time event that has no

significance beyond the Saturday on which it occurred.

1Josephus, Dissertation on Hades, passim.

2Chrysostom, Hom. Jn. 25.3 (PG 8.147c); Clement, exc. Theod. 38 (PG 9.677b).

3Andreas of Caesarea, Apoc. 59 (PG 106.408b).

4Philo of Alexandria, De congressu eruditionis gratia, 57.

5Origen, Hom. Jer. (PG 13.445, 448); Chrysostom, Hom. LXXVI; St. Symeon the New Theologian, Disc. 78.

6The association of divinity and fire was both a biblical one (e.g., Heb 12:29) and a philosophical one, reflected in the philosophy of Heraclitus and the Stoics, for example.

7Basil, Hom. Ps. 28.

8Cf. Origen, Cels. 5.16 (PG 11.1205a).

9Maximus the Confessor, Ad Thal. 59 (PG 90.609c); cf. John of Damascus, Exp. Ortho. fide 3.29 (PG 94.1101a).

10The Second Part, XXXIX, 22.

11Gregory of Nyssa, De vita Moysis, 2.82.

12Hom. Matt 36.3 (PG 7.411a).

13Chrysostom, Hom. Rom. 16.

14Irenaeus,Haer. 5.31.2 (PG 7.1209b); Athansius, Or. iii adv. Ar., 1.43 (PG 26.101b);Theodoret of Cyrus, Eranisles, 3 (PG 4.199); Basil of Caesarea, Hom. Ps. 48 (PG 29.453a); Macarius of Egypt, Hom. 11.19 (PG 34.552c); Cyril of Alexandria, Nest. 5.5 (PG 61.136d).

15Ignatius, Ep. Phil. 3, 9.

16Origen, 2nd Hom. Kings (PG 12.1021c); Chrysostom, Hom. 11 (PG 13.247a).

17Gregory of Nazianzus, Or. 43.75 (PG 36.597a); Origen, 2nd Hom. Kings (PG 12.1024a); Comm. Lk. 4.

18Origen, Hom.Gen. 15.5; engirt. 6 (PG 12.1020d); Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. 14.17, 19.

19Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. 19.4; Gregory of Nyssa, Apoll. 17 (PG 45.1156a).

20Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr. (PG 49.394-5); John of Damascus, Exp. Ortho. fide 3.29 (PG 94.1101a).

21Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr. (PG 49.394-5).

22Justin, dial. 91.4 PG 6.693b; Athanasius, Term. Fid. 13 (PG 26.1269c); Cyril of Alexandria, Jo. 4.2 (PG 73.353c).

23Cf. Chrysostom, Hom. Matt. 2.1.

24Gregory of Nyssa, Orat. cat. 23-4.

25Origen, Comm. Rom. 5.10 (PG 14.1051c-2b); Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr. (PG 49.395-6).

26Amphilochius of Iconium, Hom. 6.

27Eusebius, CH, 1.13.20; Gregory of Nazianzus, Disc. 45.1-2 (PG 36.624c); Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cross (PG 49.394-5); Epiphanius of Cyprus, Exp. fide 17 (PG 42.814c-6a).

28Origin, Comm. Jn. 6; Basil of Caesarea, Hom. Ps. 48.9 (PG 29.451-4); Pseudo-Macarius, Spiritual Hom. 11.11-3 (PG 34.552d-6a).

29Athanasius, Contra Arii. 3.56 (PG 26.441a); Amphilochius of Iconium, Hom. 6; Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr. (PG 49.395-6); Cyril of Alexandria, 7th Pasch. Hom. (PG 77.552a);

Gregory of Naz., Disc. 45.24 (PG 36.657a).

30Melito, De bapt. frag. 8b, 4.

31Clement of Alexandria, Stro. 6.6; Origen, Contra Celsus 2.43; Maximus the Confessor, Ad Thal. 7 (PG 90.284b-c); John of Damascus, Exp. Ortho. fide 3.29 (PG 94.1101a).

32Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 4.27.2.

33Clement of Alexandria, Stro. 6.6; John of Damascus, Exp. Ortho. fide 3.29 (PG 94.1101a); Maximus the Confessor, Ad Thal. 7 (PG 90.284b-c).

34See Nathan A. Jacobs, “On Whether the Soul is Immortal according to the Eastern Church Fathers,” St. Vladimir’s Quarterly, section 4.

35Maximus the Confessor, Ad Thal. 7 (PG 90.284b-c).

36PG 59.721-24.

37Methodius, Res. 2.18 (PG 18.284a).

38Chrysostom, Hom. 1 Cor. 24.7 (PG 12.142-3).

39Origen, Comm. Rom. 5.10 (PG 14.1051c-2b).

40John of Damascus, Exp. Ortho. fide 3.29 (PG 94.1101a).

41Eusebius,CH, 1.13.20; Basil, Hom. Ps. 48.9(PG 29.451-4).

42Gregory of Nyssa, De anima (v.444).

43De anima (v.833-5); Ep. Bishop Theod.

44Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr.(PG 49.394-5).

45Chrysostom, Hom. cem. cr. (PG 49.394-5).

46Pseudo-Macarius, Spiritual Hom. 11.11-3 (PG 34.552d-6a).

47Cyril of Alexandria, 7Festive Letters, 2.8; 5.1; 6.12; 11.8; 14.2; 20.4 (PG 77.848-9); 21.3 (PG 77.856a); 28.4 (PG 77.956a).

48The Eastern fathers often presume that further purification of the soul may be needed post-mortem, before the soul can rest in God (e.g., Basil, Hom. Ps. 7.2). But such a view should not be confused with the Western doctrine of Purgatory. Rather, it is merely a presumption that

restoration of the human person — body and soul — that Christ came into the world to affect is a

lifelong process, and it is not complete until the resurrection from the dead, when the body and the

soul are both restored and partake of divine immortality (see Jacobs, “On Whether the Soul is

Immortal,” section 4). The point is especially evident because the Western councils of Florence and

the Second Council of Lyons both intentionally avoided talk of place and of fire when discussing

Purgatory, knowing that the Eastern Churches would disapprove. Moreover, the Eastern

opposition to this Western doctrine is pervasive in the anti-Western polemics of Mark of Ephesus.

49One might rightly wonder in the light of this doctrine why the patriarchs of old, whowere not baptized, and thus were not delivered from the stain of original sin — baptism being the Augustinian/Western means of cleansing original sin — were able to be rescued by Christ but

infants were not.

This article is copyrighted by and published with the permission of the original author Nathan A. Jacobs, Ph.D.